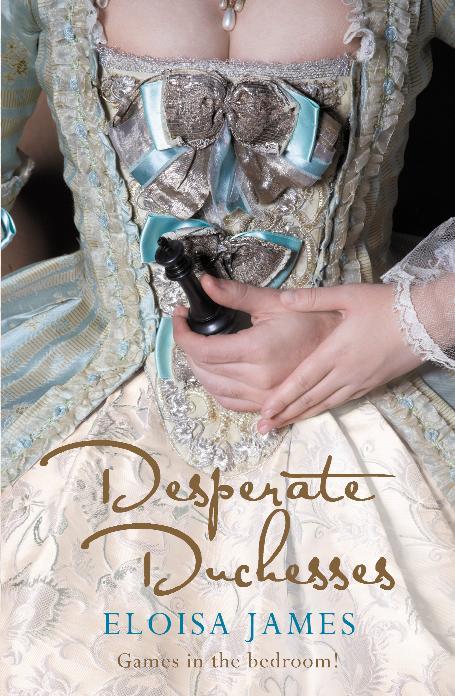

Desperate Duchesses

Book 1 in the Desperate Duchesses Series

A marquess’s sheltered only daughter, Lady Roberta St. Giles falls in love with a man she glimpses across a crowded ballroom: a duke, a chess player of consummate skill, a notorious rake who shows no interest in marriage — until he lays eyes on Roberta.

Yet the Earl of Gryffyn knows too well that the price required to gain a coronet is often too high. Damon Reeve, the earl, is determined to protect the exquisite Roberta from chasing after the wrong destiny.

Can Damon entice her into a high-stakes game of his own, even if his heart is likely to be lost in the venture?

Desperate Duchesses

Book Extras

Inside Desperate Duchesses

There’s a Shakespeare echo on page 36. Roberta says to be a duchess is consummation devoutly to be wished, but then she can’t remember where the quote came from. It’s from Hamlet in “To Be Or Not to Be” talking about death… a bleaker thing to wish for than Roberta’s comment about the title of duchess.

Stepback for Desperate Duchesses

Enjoy the stepback for Desperate Duchesses.

Extra Chapter for Desperate Duchesses

Want to know Damon’s point of view? Read the extra chapter three of Desperate Duchesses to find out!

Extra Chapter for Desperate Duchesses Series

Here’s the extra chapter that wraps up the entire Desperate Duchesses series. ~ Enjoy!

Desperate Duchesses (the Original Six) Collectible Card

Eloisa made up these gorgeous collectible cards for readers to celebrate the Desperate Duchesses, Original Six series. With Roberta and Poppy on one side and Harriet, Isidore, Jemma, and Eleanor on the other, this 5×7 can be yours. And this isn’t the only gorgeous card to be had!

Book Trailer for Desperate Duchesses

A Roberta Paper Doll

In collaboration with a very talented illustrator, Eloisa created paper dolls complete with extravagant hairpieces and two Georgian fashion dresses to go along with her Desperate Duchesses, the Original Six heroines. With the template drawn only in outline so readers could DIY, Eloisa then issued a challenge: make one and send it in, and she'd have a drawing to pick the ones that fit the heroines the best.

To see all the winning dolls and more, as well as to download the template, click over to Eloisa's Design-A-Duchess Paper Doll feature.

This is the dress Eloisa selected for Roberta. Click through to see it bigger in all its wonderful detail.

How Desperate Are You?

Ahead of the release of Desperate Duchesses, Eloisa offered an ARC (Advanced Readers Copy) to the reader who impressed her with their most wonderful answer to “How Desperate Are You?” contest. Click through for Eloisa’s most favorite responses.

Mea Culpa, Desperate Duchesses

Leelah noted that on page 125, Damon gets very self-involved. “Seduction is out of the question, then,” he says, and Roberta feels him “turn toward him.” He should turn toward her – but then you never know about men! But Damon isn’t the only self-involved character. Jenn pointed out that on page 378, Roberta says “You haven’t met him before; Roberta told me so!” In fact, Jemma told her so.

Georgian England Loved to Laugh

An essay published as a countdown to the release of Desperate Duchesses, which was a shift in setting for Eloisa from Regency England.

Desperate Duchesses

Reviews

"Slightly bawdy, totally unconventional, and thoroughly delightful..."

— Library Journal

"If Shakespeare had written an 18th-century romantic comedy, it might look something like this novel."

— Publishers Weekly

"Desperate Duchesses is a great example of why Ms. James is one of the best historical romance authors in the world.

— Romance Junkies (Blue Ribbon Rating 5)

"Ms. James does her usual excellent job of conveying the time and place with attention to authentic detail."

— Romance Reviews Today

"James does everything brilliantly."

— Romantic Times BOOKClub (Top Pick)

Desperate Duchesses

Enjoy an Excerpt

Jump to Ordering Options ↓

Listen to an Audio Excerpt ↓

Prelude

November, 1781

Estate of the Marquess of Wharton & Malmesbury

Knowing precisely why no one wants to marry you is slim consolation for the truth of it. In Lady Roberta St. Giles’s case, the evidence was all too clear – as was her lack of suitors.

The cartoon reproduced in The Rambler’s Magazine depicted Lady Roberta with a hunched back and a single brow across her bulging forehead. Her father knelt beside her, imploring passers-by to find him a respectable spouse for his daughter.

At least that part was true. Her father had fallen to his knees in the streets of Bath, precisely as depicted. To Roberta’s mind, The Rambler’s label of Mad Marquess had a certain accuracy about it as well.

“Inbreeding,” her father had said, when she flourished the magazine at him. “They assume your physique is affected by the sort of inbreeding that produces these characteristics. Interesting! After all, you could have been dangerously mad, for example, or –”

“But Papa,” she wailed, “couldn’t you make them print a retraction? I am not misshapen. Who would wish to marry me now?”

“Why, Sweetpea, you are entirely lovely,” he said, knitting his brow. “I shall write a paean on your beauty and publish it in Rambler’s. I will explain precisely why I was so distraught, and include a commentary about the practices of hardened rakehells!”

Rambler’s Magazine printed the marquess’s 818 lines of reproving verse, describing the nefarious gallant who had kissed Roberta in public without so much as a by-your-leave. They resurrected the offensive print as well. Buried somewhere in the marquess’s raging stanzas describing the peril of walking Bath’s streets was a description of his daughter: “Tell the blythe Graces as they bound, luxuriant in the buxom round, that they’re not more elegantly free, than Roberta, only daughter of a Marquess!” In vain did Roberta point out that “elegantly free” said little of the condition of her back, and that “buxom round” made her sound rather plump.

“It implies all that needs to be said,” the marquess said serenely. “Every man of sense will immediately ascertain that you have a charmingly luxurious figure, elegant features and a good dowry, not to mention your expectations from me. I cleverly pointed to your inheritance, do you see?”

All Roberta could see was a line declaring that her dowry was a peach tree.

“That’s for the rhyme,” her father had said, looking a bit cross now. “Dowry doesn’t rhyme with many words, so I had to rhyme dowry and peach tree. The tree is obviously a synecdoche.”

When Roberta looked blank, he added impatiently, “A figure of speech in which something small stands for the whole. The whole is the estate of Wharton and Malmesbury, and you know perfectly well that we have at least eleven peach trees. My nephew will inherit the estate, but the orchards are unentailed and will go to you.”

Perhaps there were clever men who deduced from the marquess’s poem that his daughter had eleven peach trees and a slender figure; not a single one of those men turned up in Wiltshire to ascertain for himself. The fact that the original cartoon remained on display in the windows of Humphrey’s Print Shop for many months may also have been a consideration.

But since the marquess refused to undertake another trip to the city wherein his daughter was accosted – “you’ll thank me for that later,” he added, rather obscurely – Lady Roberta St. Giles found herself heading quickly toward that undesirable stage of life known as “old maid.”

Two years passed. Every few months Roberta’s future would pass before her eyes, a life spent copying and cataloguing her father’s poems, when not alphabetizing rejection letters from publishers for use by the marquess’s future biographers, and she would rebel. In vain did she reason, implore or cry. Even threatening to burn every poem in the house had no effect; it wasn’t until she snatched a copy of “For the Custards Mary Brought Me” and threw it in the fire that her father understood her seriousness.

And only by withholding the single remaining copy of the Custard poem did she gain permission to attend the New Year’s ball being held by Lady Cholmondelay.

“We’ll have to stay overnight,” her father said, his lower lip jutting out with disapproval.

“We’ll go by ourselves,” Roberta said. “Without Mrs. Grope.”

“Without Mrs. Grope!” He opened his mouth to bellow, but —

“Papa, you do want me to have some attention, don’t you? Mrs. Grope will cast me entirely in the shade.”

“Humph.”

“I shall need a new dress.”

“An excellent thought. I was in the village the other day and one of Mrs. Parthnell’s children was running about the square looking blue with cold. I’ve no doubt but that she could use your custom.”

She barely opened her mouth before he lifted his hand. “You wouldn’t want a gown from some other mantua-maker, dearest. You’re not thinking of poor Mrs. Parthnell and her eight children.”

“I am thinking,” Roberta said, “of Mrs. Parthnell’s bungled bodices.”

But her father frowned at that, since he had strong views about the shallow nature of fashion and even stronger views about supporting the villagers, no matter how inferior their products.

Unfortunately, the New Year’s ball produced no suitors.

Papa could not forbear from bringing Mrs. Grope – “’twill hurt her feelings too much, my dear” – and consequently, Roberta spent the evening watching revelers titter at the presence of a notorious strumpet amongst them. No one appeared to be interested in whether the Mad Marquess’s daughter had a humped back or not; they were too busy peering at the Mad Marquess’s courtesan. Their hostess was incensed at her father’s rudeness in bringing his chère-amie to her ball, and wasted none of her precious time introducing Roberta to young men.

Her father danced with Mrs. Grope; Roberta sat at the side of the room and watched. Mrs. Grope’s hair was adorned with ribbons, feathers, flowers, jewels and a bird made from papier mâché. This made it easy for Roberta to pretend that she didn’t know her own parent; when the said plumage headed in her direction, Roberta would slip away for a brisk stroll. She visited the ladies’ retiring room so many times that the company likely thought she had a female complaint to match her invisible hump.

Around eleven o’clock, a gentleman finally asked her to dance. But he turned out to be Lady Cholmondelay’s curate, and he immediately launched into a confused lecture to do with notorious strumpets. He seemed to be equating Mrs. Grope to Mary Magdalene, but the dance kept separating them before Roberta could grasp the connection.

Unfortunately, they came face-to-face with the marquess and Mrs. Grope just when the curate was detailing his feelings about trollops.

“I take your meaning, sirrah, and Mrs. Grope is no trollop!” the marquess snapped. Roberta’s heart sank and she tried vainly to turn her partner in the opposite direction.

But the plump little pigeon of a man dug in his heels, squared his shoulders and retorted, “Muse upon my comments at your leisure, or woe betide your eternal soul!”

Everyone in the immediate vicinity stopped dancing, grasping that a more interesting performance had begun.

The marquess did not disappoint them. “Mrs. Grope is a lovely woman, kind enough to accept my adoration,” Roberta’s father roared, loud enough so that no one in the room could miss a word. “She is no more a trollop than is my own daughter, the treasure of my house!”

Predictably, the crowd turned as one to examine the signs of trollopdom, the first interest shown Roberta all evening. With a gasp, she fled back to the ladies’ retiring room.

Within a half hour, Roberta made several important decisions. The first was that she’s had enough humiliation. She wanted a husband who would never, under any circumstances, make a public display of himself or those around him. And he should know nothing of poetry. Second, her only chance of finding that husband was to make her way to London without her father or Mrs. Grope. She would go there, pick an appropriate gentleman and arrange to marry him. Somehow.

She returned to her seat in the corner with renewed interest and began surveying the company for the appropriate characteristics.

“Who is that gentleman?” she asked a passing footman, who had given her a few pitying glances during the evening.

He said, “Which one, miss?” He had a nice smile and looked as if his wig itched.

“The man in the green coat.” To call it green was faint praise: it was a pale, pale green, embroidered with black flowers. It was the most exquisite garment she had ever seen. The man was tall and moved with the careless grace of an athlete. He wore no wig, unlike the other perspiring gentlemen pacing through the dance. His hair was a rumpled black, shot with two or three brilliant streaks of white, and tied at his neck with a pale green ribbon. He was a dangerous mixture of carelessness and supreme elegance.

The footman handed her a glass in order to disguise the fact they were speaking. “That’s His Grace, the Duke of Villiers. He plays chess. Hadn’t you heard of him then?”

She shook her head and took the glass.

“They do say he’s the best for chess in England,” the footman said. He leaned a bit closer and said, eyes dancing, ” Lady Cholmondelay thinks he’s the best at sport, if you’ll forgive my presumption.”

A snort of laughter escaped Roberta’s mouth before she could stop herself.

“I’ve watched you this eve,” he said. “Tapping your foot. We’ve our own ball below stairs. And it seems no one knows you here. Why don’t you come back there and dance a round with me?”

“I couldn’t! Someone would –” She looked around. The room was crowded with laughing, dancing peers. No one had paid any attention to her, or even spoken to her in over an hour. Her papa had wandered off again with Mrs. Grope, content to think that she was “hunting prey,” as he put it in the carriage.

“Below stairs, they won’t know you’re a lady,” the footman said, “not in that dress, miss. They’ll think you’re a lady’s maid. At least that way you can have a dance!”

“All right,” she whispered.

For the first time all evening, young men bowed before her. She invented an irascible mistress and had great fun describing her tribulations dressing her. She danced twice with “her” footman and separately with three more. Finally, she realized that there was a remote possibility that her father would miss her, and she headed back to the ball.

Then she realized there was also the possibility that he would have forgotten about her and left for the inn.

She ran down the corridor, slammed open the baize door that marked the servants’ quarters – and knocked over the Duke of Villiers.

He stared at her from the ground, with eyes as cold as spring rainfall. Then he said without stirring, in a husky, drawling voice that made her shiver all over, “You must tell the butler to train you in proper behavior.”

She blushed and dropped a curtsy, dazed by the pure raw masculinity of him, by his hollowed cheeks and jaded look. He was everything that her father was not. There wasn’t an ounce of sentiment in him. A man like that would never embarrass himself.

Life with her father had taught her to be blunt about her own emotions, or risk having them dissected by a poet. So she knew instantly what it was she felt: lust. Her father’s poetry on the subject filtered through her mind, confirming her sense.

He stood and then tipped up her chin. “An astonishing beauty to find in such a dim squirrel’s hole as the servants’ quarters.”

Roberta felt a thrill of triumph. Apparently he didn’t think that she had a beetle brow or a humped back. The lust was mutual. “Ah –” she said, trying to think what to say other than a blunt proposal.

“Red hair,” he said, rather dreamily. “Extraordinary high arches of eyebrows, slightly tilted eyes. A deep ruby for a lower lip. I could paint you in water colors.”

His catalog raised Roberta’s hackles a little; she felt like a horse he was considering for purchase. “I should prefer not to look blurry; could you not manage oils?” she asked.

He raised an eyebrow. “No maid’s apron, and the voice of a lady. I fear I misjudged your station.”

“As a matter of fact, I am rejoining my family in the ballroom.”

His eyes skittered over the plain laced front of her gown, with its misshapen pleats that looked as if she had fashioned them herself.

He dropped his hand. “That makes you altogether more delectable and forbidden fare, an impoverished noblewoman. I would have you without delay if you had but a few pennies to your name, my dear, but even I have a few paltry morals. Foibles, really.”

“You assume a great deal,” she had said. She meant that he was assuming she was poor, although the supposition was fair enough, given her clothing. But he jumped to the more obvious meaning.

“‘Tis true you might not have me. Though I’ll tell you the secret to my success with women, and I won’t charge you ha’pence since you haven’t an extra one to your purse.”

She waited, cataloguing the sheen of his coat and the rumpled perfection of his hair.

“I don’t really give a damn whether I have you or not.”

“You shan’t have me,” she said, stung. “Because I feel precisely the same way about you.”

“In that case, I will kiss your fingertips and retire.”

As he made a leg before her, she watched the skirts of his coat fall into perfect pleats. Not for nothing was she a wordsmith’s daughter. Pale green wasn’t descriptive enough; the silk taffeta of his coat was celadon, the green of the new leaves. And its black embroidery, on close inspection, was mulberry-colored.

It was an exquisite combination. Enough to change her mind entirely. What she felt was entirely too deep for a flimsy emotion such as lust.

What she felt wasn’t lust – it was love. For the first time in her life. . . she was in love.

In love!

“I’m going to London,” she told her father once they were home again. “My heart is in chains and I must follow its call.” Though such extravagant language was definitely not Roberta’s chosen mode of expression, she felt that quoting one of her father’s poems was a sound precaution.

“You most certainly are not!” he said, ignoring her literary reference. “I will –”

“Without you,” she said. “And without Mrs. Grope.”

“Absolutely not!”

They battled on for a month or so until March edition of The Rambler’s Magazine arrived in the post.

These etchings were no more accurate than those of two year earlier. She was humped-backed and fiercely browed, on her knees before a man in livery, presumably praying for the footman’s hand in marriage. “Like father, like daughter,” the inscription read. “We always suspected that desperation was hereditary.”

Roberta had no doubt that the image was selling briskly in Humphrey’s Print Shop.

“My conscience is clear!” her father bellowed, once he understood the reference. “Surely you could have guessed that servants are in the pay of gossip rags? How could you not, given the fact that Mrs. Grope and myself make such frequent appearances in Town and Country? Someone made a pretty penny from your folly. It’s no good begging me to write another poem; the powers of my literature would be of no avail.”

The marquess’s rage was assuaged only after writing four hundred lines of iambic pentameter rhyming “serpent’s tooth” and “daughter,” which is no easy feat.

His daughter’s distress was diminished only by repeating to herself that she was going to marry the Duke of Villiers, order clothes of celadon silk, and never listen to another poem again in her life.

She commandeered her father’s second-best coach and the second-upstairs housemaid to accompany her to London and left, clutching a valise filled with Mrs. Parthnell’s unsightly clothing, a measured sum of money, and a poem from her father, which was the only introduction he would vouchsafe her.

“Oh, brave new world!” she whispered to herself. And then wrinkled her nose. No more poetry. The Duke of Villiers had likely never heard of John Donne and probably couldn’t tell a roundelay from a rickshaw.

He was perfect.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Chapter One

April 10, 1783

Beaumont House, Kensington

“In Paris, a married lady must have a lover or she is an unknown. And she may be pardoned two.” The door to the drawing room swung open, but the young woman sitting with her back to the door took no notice.

“Two?” an exquisitely dressed young man remarked. “I gathered that Frenchmen are a happy race of men. They seemed so petulant to me when I was last there. It must be the embarrassment of riches, like having three custards after supper.”

“Three lovers are considered rather too many,” the woman replied. “Although I have known some who considered three to be a privilege rather than an abundance.” Her low laugh was a type that tickled a man’s breastbone and even lower. It said volumes about her personal abilities to manage one – or three — Frenchmen with aplomb.

Her husband closed the door behind him and stepped into the room.

The young man glanced up and came to his feet, bowing without extraordinary haste. “Your Grace.”

“Lord Corbin,” the Duke of Beaumont replied, bowing. Corbin was just Jemma’s taste: elegant, assured, and far more intelligent than he admitted. In fact, he would make a good man in parliament, not that Corbin would lower himself to something approaching work.

His brother-in-law, the Earl of Gryffyn, rose and made him a casual bow.

“Your servant, Gryffyn,” the duke said, making a leg.

“Do join us, Beaumont,” his wife said, looking up at him with an expression of the utmost friendliness. “It’s a pleasure to see you. Is the House of Lords not meeting today?” That was part and parcel with the war they had waged for the last eight years: conversation embroidered with delicate barbs, rarely with coarse emotion.

“It is in session, but I thought to spend some time with you. After all, you have barely returned from Paris.” The duke bared his teeth in an approximation of a smile.

“I miss it already,” Jemma said, with a lavish sigh. “It’s marvelous that you’re here, darling,” she said, leaning forward a bit and tapping him on the hand with her fan. “I’m just waiting for Harriet, the Duchess of Berrow, to arrive. And then we shall make a decision about the centerpiece for tomorrow’s fête.”

“Fowle tells me that we are holding a ball.” The duke – who thought of himself as Elijah, though he would be very affronted were any person to address him so – kept his voice even. Those years of parliamentary debate were going to prove useful, now that Jemma had returned to London. ‘Twas the reason he’d stayed home for the day, if truth be told. He had to strike a bargain with his wife that would curb her activities to an acceptable level. And he wouldn’t get there by losing his temper; he remembered their newlywed battles well enough.

“Dear me, don’t tell me that I forgot to inform you! I know it’s a bit mad, but the plans gave me something to do on the voyage here.”

She looked genuinely repentant, and indeed, for all Elijah knew, she was. The game of marriage they played required strictly friendly manners in public. Not that they were ever in private.

“He just did tell you that,” her brother put in. “You’d better watch out, Sis. You’re not used to sharing a household.”

“It was truly ill-mannered of me,” she said, leaping to her feet, which made her silk petticoats swirl around her narrow ankles. She was dressed in a pale blue gown à la Française, embroidered all over with forget-me-nots. Her bodice caressed every curve of her breasts and narrow waist before the skirts billowed over her panniers.

By all rights, the way her side hoops concealed the swell of her hips should be distasteful to a man, and yet Elijah had to admit that they played an irresistible part in a man’s imagination, leading the eye from the curve of a breast to the narrow waist, and then driving him perforce to imagine slender limbs and – and the rest of it.

Jemma held out her hand; Elijah paused for a moment and then took it. She smiled at him, as a mother might smile at a little boy reluctant to wash his face. “I am so glad that you are able to join us this morning, Beaumont. While I trust that these gentlemen have impeccable opinions –” she cast a glimmering smile at Corbin – “one’s husband’s opinion must, of course, carry sway. I do declare that it’s been so long since I felt as if I had a husband that it is quite a novelty! I shall probably bore you to tears asking you to approve my ribbons.”

In the old days, the first days of their marriage, Elijah would have bristled. But he was seasoned by years of dedicated jousting in Parliament where the stakes were more important than ribbons and trifles. “I am quite certain that Corbin can do my duty with your ribbons.” He said it with just the right amount of disinterest and courtesy in his voice.

From the corner of his eye, Elijah noticed that Corbin didn’t even blink at the idea he had just been invited by a duke to do his husbandly duty. Perhaps the man could keep Jemma occupied enough that she wouldn’t cause too many scandals before parliament went into recess. He turned sharply toward the door, annoyed to discover that his wife’s beauty seemed more potent in his own house than it had been in Paris during his rare visits.

Partly it was because Jemma had not powdered her hair. She knew quite well that the shimmer of weathered gold was far more enticing than powder, and contrasted better with her blue eyes. It was only – he told himself – because she was his wife that he felt this prickling irritation at her beauty. Or perhaps the irritation was caused by her self-possession. When they first married, she wasn’t so flawless. Now everything about her was polished to perfection, from the color of her lip to the witty edge of her comments.

Those blue eyes of hers widened just slightly, and she cast him another of her glimmering smiles. “We really are two hearts that beat as one, Beaumont,” she said.

“In that case,” her brother said, “It is truly odd that you have spent so much time apart. Not to break up this touching example at marital felicity – so rare in our depraved age and, I think we’ll all agree, an inspiration to us all – but can you just show us the damned centerpiece now, Jemma? I’ve got an appointment on Bond Street, and your friend the duchess doesn’t seem to be making an appearance.”

“It’s just in the next room, if Caro has everything prepared. She wasn’t quite ready when you arrived.”

Elijah caught himself before asking who Caro was.

Jemma was still speaking. “I trust her with everything. She has the most elegant eye of any female I’ve ever known. Except, perhaps, Her Majesty, Queen Marie Antoinette.”

Elijah shot his wife a look that showed exactly what he felt about those who boasted of intimacy with French royalty. “Shall we examine this centerpiece, sirs?” he said, turning to Corbin and Gryffyn. “The duchess is considered quite a leader of fashion in Paris. I myself shall never forget her masquerade ball of ’79.”

“Were you there?” Jemma asked wonderingly. “I vow, I had quite forgotten. She tapped him on the arm with her fan. “Now it comes back to me. All the men were dressed as satyrs ’twas most ravishingly amusing but you wore black and white, for all the world like a parliamentary penguin.”

He dropped her hand, so that he could bow again. “Alas, I do not show to best advantage with a satyr’s tail.” And neither did the asses of Frenchmen, though he didn’t say it aloud.

She sighed. “Both members of my family declined to join the fun. So English so pompous so ”

“So clothed,” Gryffyn said. “There were some knees in evidence that night that should never have seen the light of day. I still have trouble forgetting Le Comte dAuvergnes bony knobs.”

Jemma peeked through the doors to the ballroom beyond. Then she laughed and flung them open. “How wonderful it all looks, Caro! You are brilliant, absolutely brilliant, as always!”

Corbin was briskly following in Jemma’s train, so Elijah grabbed his brother-in-law’s elbow. “Who the hell is Caro?”

“Pestilently intelligent woman,” Gryffyn said. “Jemma’s secretary. She’s been around for four or five years. You haven’t encountered her?”

And, at Elijah’s shrug, “She prepares Jemma’s most extravagant escapades. Accomplices in scandal, that’s the way to describe them. Prepare to be dazzled by her incomparable abilities, not that you’ll appreciate them. I don’t suppose that you’re secretly hoping that Jemma will transform into a political wife, are you?”

“My hope is limited to a wish that she doesn’t topple my career,” Elijah said. “Do I mean you to say that all of Jemma’s secretary’s abilities are directed to the creation of scandal?”

“As I said, you won’t like it,” Gryffyn said. They were at the door. He pulled it farther open and moved to the side. “This is pretty standard for her.”

Elijah walked through the door and stopped short.

“Bloody hell,” he breathed.

“It’s better than those satyrs. No tail,” Gryffyn pointed out.

As Elijah stared into the room, he felt his hard-won calm and control slipping from his grasp. The huge mahogany table that generally stood in the dining room had been removed to the middle of the ballroom. Rather than dishes, it held an enormous pink shell, apparently made of clay. Rosebuds were strewn all about, falling in chains to the floor. Numbly he noticed that Jemma was exclaiming over how realistic the flowers appeared. “And the sea shells!” she squealed. “A beautiful touch, Caro!”

But that wasn’t it, of course.

What was making his blood thud against the wall of his chest wasn’t the hundreds of pounds worth of fabric flowers, nor the shell, nor even the pearls, because there were also strings and strings of pearls. God knows, he had more than enough money for whatever extravagances Jemma came up with. What Elijah treasured more than anything else in the world was his stock of carefully nourished, tenderly used, political power.

He had nurtured it day by day. Built up a solid reputation for energetic, thoughtful argument. While his wife lived in Paris for the last eight years, he built a career without the help that other men got from their wives throwing dinner parties, or hosting salons. He’d come to the top of the House of Lords, to one of the most respected positions in the kingdom, by marshalling his intellect, never taking a bribe. Separating himself from the corrupt policies and wild scandals that plagued Fox and the Prince of Wales’s disgraceful cronies.

And now, when he might have only a little time left to further his work —

The centerpiece wasn’t wearing a damned scrap of clothing.

And she was painted gold; never mind the pearls that were glued around her body at regular intervals.

His brother-in-law was watching her with a calculated, lustful look in his eye that Elijah despised, though he had to admit that only a dead man would ignore this centerpiece.

“At least she’s not wearing a tail,” Gryffyn commented.

At that very moment, the naked, gold-painted young lady bent sideways and fiddled with the little stand on which she was leaning. A huge spray of gorgeous peacock feathers burst from behind her beautifully curved rear.

“Spoke too soon,” Gryffyn said happily.

“Damn it to hell,” Elijah breathed.

end of excerpt

Desperate Duchesses

by Eloisa James

is available in the following formats:

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.