Bookcode: her-own

Desperate Duchesses Printable Bookmarks

Enjoy these printable bookmarks featuring This Duchess of Mine and A Duke of Her Own!

Click to see a bigger version that can be printed if you’d like.

Extra Chapter for Desperate Duchesses Series

May 1791 (a short time before the Epilogue of A Duke of Her Own)

The London residence of the Duke of Villiers

15, Piccadilly

Everyone in the house – about fifty-eight souls – knew the Duchess of Villiers was in labor; mortifying though it was, Eleanor was perfectly aware of the public status of her condition.

The fact could hardly be kept private when one’s water breaks unexpectedly in the breakfast room. One minute Eleanor was greeting their butler, Ashmole, good morning, and the next she was surrounded by an unpleasantly warm puddle of water.

Ashmole’s face didn’t even twitch. His eyes followed her astonished gaze to the floor, his head snapped up, and he began dispatching footmen in all directions: to the accoucheur, midwife, Eleanor’s maid, her sister, her —

“Not my mother,” Eleanor interrupted. She knew she had turned rather pink, but she picked up her skirts and sailed – not an inappropriate metaphor under the circumstances – up the stairs without meeting the eyes of any of those footmen, nor her butler, nor her husband.

She couldn’t have done the last anyway, as the duke was behind her, pushing her up the stairs as fast as he could, apparently worried that the babe would plop onto the floor.

At the top of the stairs, Leopold rushed before her, the better to tow her through the door (ho ho) and deposit her on the bed.

“Lie still,” he commanded, turning to pull the bell so fiercely that the cord snapped off in his hand.

She took advantage of his startled curse to roll off the other side of the bed.

“You shouldn’t be standing up!” he said, heading toward her as if he intended to pin her onto the bed.

But Eleanor, who was inexperienced rather than unintelligent, had just realized that the nasty backache that had kept her awake all night was not merely an ache. In fact, it couldn’t be catalogued under that word at all; it was rapidly turning into something quite different, more along the lines of an encounter with boiling oil.

She reached out just in time, grabbed the bedpost and managed to say, “Don’t touch me,” between clenched teeth.

Leopold froze.

“All right,” she panted, a moment later. When he didn’t answer immediately, she realized that her beloved husband had turned quite…well, white wasn’t the right word. More greenish. With an interesting purple tint under his eyes. You’d think he was the sleepless one, whereas she knew for a fact that he’d slept like the proverbial baby since she had been awake to catalog the passing hours.

“You’re in pain,” he said, showing a level of intelligence that she could only hope would be surpassed in their offspring.

“I don’t want a crowd of people in here, Leopold,” she told him. “I’m not the queen.” Poor Queen Charlotte delivered all her babies before a crowd, a fact Eleanor had absorbed with horror. “And keep that accoucheur out; he’s a pompous idiot.”

At that very moment the door opened and a tidal wave of women poured into the room.

“I can’t –“ Eleanor gasped, realizing that there was another bout of pain starting at her toes. Or it would be accurate to say that it started at her thighs and swept upwards.

She turned to the only person whose face she could see clearly, grabbed the bedpost again and told him with a ferocity that female royalty would certainly envy, “Get them out of here!”

“All but the midwife,” Leopold bargained. His eyes looked rather wild. “If not the accoucheur, the midwife. She probably needs to…look at you or something.”

Eleanor gripped the bedpost so hard that she was surprised it didn’t splinter. “I’m not the queen,” she said, not making much sense but they both knew what she meant.

The life of a duchess is lived in public. Eleanor knew that and accepted it. Most of the time, she quite liked it. What woman in her right mind wouldn’t enjoy the cheerful company of a houseful of people bent on pleasing her?

But this was different. The pain made Eleanor feel like mooing like a cow and she intended to do that alone.

“Get them out,” she said, hissing it like a teakettle about to explode.

When the contraction was over, Leopold eased her back on the bed. “Just let the midwife examine you for a moment,” he pleaded. “I promise that they’ll leave you alone. Look, the wet nurse is gone, and the maids too.”

She caught her breath, hardly listening as Leopold informed the midwife that no, he wasn’t leaving until his wife asked him to, and then informed the woman she had exactly one minute to make her examination because, he said, “The duchess wants you out of the room.”

If there was one thing the Duke of Villiers was excellent at (and privately, Eleanor thought there were quite a few), it was terrifying the unwary into compliance. It took a few minutes, and another contraction, but the protesting midwife found herself on the opposite side of the door.

Eleanor managed to pull herself upright again. It felt better that way. She hung onto the bedpost through another contraction.

“Walk,” she gasped, once she had control of her lungs again.

“Where?”

She pushed Leopold out of the way. If he wouldn’t help her, she’d walk on her own. She’d never felt like this before: in the grip of something bigger than herself.

“Where are the children?” she croaked.

“You had them sent to the country two days ago,” Leopold said. “Don’t you remember? Eleanor, are you sure –“

He was grabbing at her again, so she swatted him off. “I’m going to walk.” With that she made her way, like a rather large and over-burdened tugboat, around the end of the bed. She opened the door to find a perfect wilderness of women hovering in the hallway.

From behind her she heard one word from her husband, a word which distilled years, nay centuries, of dukedom into one command: “Out!”

They fled.

The picture gallery, Eleanor decided. It was long and quiet.

Leopold was walking backwards before her. “Darling, where are you going?” he said, calmly enough, given that his hands were visibly shaking.

“The gallery,” Eleanor managed, but then she had to stop and hang onto him. She felt as if she were in a huge storm at sea, and he were the mast.

Two hours later, they were making their fortieth turn down the gallery when she realized that the storm was entirely Leopold’s fault. She told him that, between contractions.

“You’re right,” he said soothingly.

“Don’t talk to me as if I were an old woman in need of lies! You sound like a monkey’s arse!” It was the rudest phrase she could come up with. “I’m never doing this again. Never. Don’t say a word to me… Owww!”

When the pain stopped wrenching its way down her legs, she realized that she had actually ripped the shoulder off from Leopold’s linen shirt. “You shouldn’t wear such fine clothes. Not when –“

She broke off. “I think we need the midwife now.”

“Not here,” Leopold said between clenched teeth. He swept her into his arms.

“Don’t drop me!” Eleanor squeaked.

“Never,” he said, carefully walking the length of the gallery. He maneuvered her through the door, down the corridor, and back into her bedchamber. He stuck his head back out the door for a second to bellow “Mrs. Bannockburn!”

“Hell’s bells,” Eleanor gasped. She felt like arching her back, so she did that.

The midwife tumbled in the door, saying something idiotic about the baby not being likely for hours yet.

“It’s already been hours. She’s coming now,” Eleanor snarled. She could feel a sweaty lock of hair sticking to her forehead.

“New mothers!” Mrs. Bannockburn said, clucking. “Always think they know what’s what…babies take their own time.”

“Wash your hands before you touch my wife,” Leopold snapped.

Mrs. Bannockburn turned a little ruddy. “I always wash my hands. Now I’ll just have a peek and see whether we’ve made any progress.”

“You haven’t made any,” Eleanor growled. “But I’ve made a lot.”

One quick look under Eleanor’s chemise and Mrs. Bannockburn’s face changed.

“We’re about to have a baby here, Your Grace,” she told the duke, deftly snatching towels from a waiting stack and tucking them under Eleanor’s bottom. “May I request that Your Grace leave the room now? This is a matter for women.”

“Out!” Eleanor managed with something of an echo of Leopold’s own command.

He leaned down and took her face in his hands. “I don’t deserve to be anywhere near you, darling. I’ve never seen such courage.”

She managed a smile and then he was gone. Eleanor arched her back again. “I have to –“

From the corner of her eye she saw Mrs. Bannockburn push her husband from the room.

Then the midwife was back, her voice suddenly soothing. “I see a bonny little head, Your Grace,” she said. “I want you to focus on me. See me? Do you see me?”

Authority had moved from Leopold, to Eleanor, to Mrs. Bannockburn. The midwife was unquestionably in charge.

Eleanor managed some sort of gasp in reply.

“Wait for it,” Mrs. Bannockburn said. “Wait…wait…now. Push, Your Grace. Push like you’ve never pushed before.”

I’ve never… Eleanor thought, but lost the words. I’ve never…

Some time later she still hadn’t finished the thought, but she was staring down at ruddy, bald head. “I’ve never seen such an ugly baby,” she said suddenly.

“Oh tush,” Mrs. Bannockburn said. “I’ve seen much worse. Besides, it wouldn’t be fair to all the other babies born today if he were handsome. He’ll be a duke and that’ll get him a woman in his bed if he turns out as skinny as a rooster.”

“Leopold has to see him,” Eleanor said, touching the baby’s blotchy cheek. “This nose is his fault. And his lip? What happened to his upper lip? There’s no one in my family who has such a thin mouth. Why doesn’t he open his eyes?”

“Don’t worry about that. He’s a bit tired, but he’s breathing nicely. Babies tend to look like that. He’ll have a lovely little mouth, you’ll see. Let me just clean up a trifle more and bring in your maid, and then we’ll have His Grace in to see his son.”

Eleanor stared down at the child. She’d been so certain she was carrying a girl. But instead she had been totting around a plump bald boy with a nose that resembled nothing so much as a potato. As she watched he finally opened his eyes.

They were the color of cornflowers. He peered at her, rather puzzled…

“Hello,” she said. Something twanged in the area of her heart.

There was a whisper of motion next to her and she looked up to see Leopold, his hair fallen from his ribbon and his shirt still ripped at the shoulder. He was staring down at the child and suddenly she knew exactly where that nose had come from.

She started laughing. “He’s going to look just like you, Leopold.”

“I feel as if I should apologize to him already,” Leopold said. “Though I assure you that my head is quite flat on top. He’ll have to go to Almack’s in a stocking cap to cover it up that pointed bit.”

Mrs. Bannockburn laughed. “It’ll sort itself out,” she said. “Now Your Grace, I’ll ask you to take the babe outside for a moment or two while Her Grace and I finish up.”

“No,” Eleanor said, her arms tightening. “I don’t want to let him go yet.”

“And I don’t want to hold him,” Leopold said, backing off. “He’s absurdly small.”

“I’m sorry, Your Grace,” Mrs. Bannockburn said to Eleanor, “but I need your attention. I’ll call the wet-nurse, shall I?”

“I’m nursing him myself,” Eleanor said, making up her mind that very moment. For the baby was still looking at her. And while he would never, ever be beautiful, he was somehow…beautiful.

“I’m going to have to buy him a wife,” Leopold said, echoing her thought. “He’ll never find one on his own.”

“He can live with us forever,” Eleanor said. “Look at his sweet little cheeks, Leopold. And he has the most darling fingers. Just look how they curled around my finger. I think he’s very, very bright.”

“It would be handy,” Leopold said, still looking at the baby. “Have you looked over the rest of him? Are all his male parts in order?”

She couldn’t help a little grin. “They’re as big as his nose. Bigger!”

“Your Grace,” Mrs. Bannockburn said patiently.

“You take him, Leopold,” Eleanor said. “I don’t want anyone else touching him yet. Just the two of us.” She watched him carry the baby out the door as gingerly as if he were carrying a crystal egg.

A half-hour later Mrs. Bannockburn allowed that she could have the baby back. When Leopold came in, Eleanor was sitting up, feeling exhausted but clean, in a snowy white chemise.

There was something different about Leopold’s face when he walked in: something fierce, and proud. “Look at this,” he said, sitting down on the edge of the bed but not giving the baby back. “He’s opening his mouth like a little fish. He’s going to be talking soon.” He beamed down at him.

Eleanor couldn’t help it; the joy welled up in her heart until she started laughing and couldn’t stop.

“I sent for the children,” Leopold said. “They’ll love this. Look, he’s opening his mouth again, just like a little doll.”

“He’s – “ But a sudden bellow from the little doll interrupted Mrs. Bannockburn’s comment.

“Hungry,” she continued.

The christening of Theodore, future Duke of Villiers, took place a few weeks later. By then Leopold and Eleanor had grown accustomed to less sleep and more joy. Leopold spent most of his time arranging for the baptism; Eleanor spent most of hers trying to keep her insatiable son fed.

She was lolling in bed the day before the baptism when he came in to enumerate the final details. “They’ll all be baptized one after another,” he told her, “except for the twins who insist on being baptized together. So the Bishop and the Dean will step forward and do them at the same time.”

Theodore burped loudly.

“I’ll have to rely on Ashmole to keep the godparents in proper order in the back of the cathedral. I’m afraid there’s going to be a lot of people. I just hope we made the right decision by making the ceremony public.”

“We knew people would be interested,” Eleanor said sleepily. “It’s not often that a duke decides to baptize all of his children at once.”

“Well, I can’t be sure the others were baptized,” he told her, once again. “How could I baptize Theodore if I might have missed one of the others? Besides the Bishop assures me that too much baptismal water is better than too little.”

Leopold paused for a moment, staring down at the baby. “Remember how ugly he was at first?”

Theodore was sleeping, his mouth pursed like a plump, beautiful rosebud. His head was perfectly round, and even his nose seemed to have diminished a bit. “He was never ugly,” Eleanor said, and then started to laugh. “Well, perhaps he was.”

The christening was a very grand affair. Leopold had decided that everything to do with his illegitimate children would be conducted with the utmost pomp and ceremony, thereby ensuring that the ton realized that the full weight of his power lay behind each and every child. They were dressed like little princes and princesses, all the way from Tobias to the twins.

The Duke and Duchess of Beaumont were the first to arrive, sweeping into the anti-room with the kind of air of splendor and excitement that always accompanied them. Not to mention the squeals of their own children, who pounced on their favorite play mates.

“Stay off, you little monster,” Jemma called to her eldest child. “Evan! Can’t you see that Lucinda is far too elegant for such rough play? For goodness sake, Villiers. Do you have that child in cloth of gold?”

“They all are,” Villiers said imperturbably. He himself was dressed with wild magnificence, in black velvet embroidered with pearls.

“Tell me again,” Elijah said. “Just who am I godfathering?”

“You have Tobias,” Leopold said, pulling his eldest son to his side. “He needs you the most because he’s the most wicked. And you –“ he gave Elijah a lopsided smile, “—are such a sanctimonious type that I’m hopeful you’ll rub off on him.”

At twenty, Tobias was at Oxford along with his brother Colin, and though he still had the lean figure of a very young man, he was as naturally graceful and dignified as someone much older. The product of his upbringing, Leopold and Eleanor told each other.

Leopold left Tobias with Elijah and Jemma, and caught Violet. She was quietly watching the children racing around the room, a sweet little smile on her face. She was the child he worried about the most, he thought, because she would never demand what she most needed.

He reached out and plucked the Duke and Duchess of Cosway from the midst of the hoards of children now crowding the vestry. “You two,” he said, “will be godparents to Violet.”

Violet blushed with all the violence of a thirteen-year-old girl, and dropped a curtsy.

Isidore held out her hand, with that lavish, mischievous smile that won the hearts of all who knew her. “Darling Villiers, you’ve made me so happy. I’m absolutely outnumbered in our household,” she told Violet. “I have these two naughty scraps who happen to be male, and Lucia and I run around madly just trying to make ourselves heard.” She wrapped an arm around Violet. “Now whenever you’re with us, Lucia, you and I can range ourselves against Dante, Pietro and the duke, and we’ll win all the games.”

Simeon snorted. “Don’t count on it,” he told Violet. “The other week she smashed a cricket ball straight through one of the windows.”

Leopold watched Violet relaxing into the curve of Isidore’s arm and turned away with satisfaction.

He got hold of his second son, Colin, by dint of pulling him out from under a heap of little boys, most of whom were future dukes. Colin was eighteen and full of laughter; unlike Tobias, he was unmarked by his early childhood. In fact, he liked to tell romantic stories to the other children about his days as a weaver’s apprentice. Leopold marched him over to the Earl of Gryffyn and his lovely wife, Roberta.

Damon turned around with a grin. “That boy is going to be taller than you are, Villiers,” he said.

“This is your new godson,” Leopold said.

“Colin!” Damon said. “How are you doing at Christ Church?”

“The porters still point out your room to all the first years,” Colin said with an impudent twinkle that mirrored Damon’s.

“Famous, am I?” Damon said.

“Infamous, I’ve no doubt,” his beautiful wife Roberta put in.

Colin turned to her. “He put a turkey in the bed of the head of college. It was stuffed with dead fish, and then he let in three cats in the middle of the night.”

“Pooh,” Damon said. “That was just my first year, and it was five cats. Wait til I tell you what I did to the statue of Mercury that stands in Tom Quad.”

Leopold eased away. That was Tobias, Colin, Violet… Genevieve, Lucinda and Phoebe left. He found the girls easily enough, by locating his wife and the baby. He stood for a moment, watching them coo at the child.

Genevieve had grown up in the country, with her mother. Even after he located all of his missing children and brought them home, he never took her from her mother, although he bought them a snug little house and all the comforts they could wish.

And when Genevieve’s mother died a year later, it was very sad – but not tragic, because then Genevieve came to them for more than a holiday. In the beginning, she attached herself to Eleanor like a limpet, but in time she became the peacemaker, the child who stood between Violet’s and Lucinda’s most violent quarrels.

He brought her to Harriet and Jem Strange (also known as the Marquis and Marchioness of Broadham). Harriet greeted Genevieve with delight. “I haven’t seen you since Twelfth Night.”

“How is my chicken?” Genevieve said, smiling shyly.

“Hale and hearty,” Harriet said. “Peters would love to cook him for supper, but I’ve told him that after surviving the terror of being a prize at Bartholomew Fair your chicken deserves to live to old age.”

“Plus,” Jem said, joining them, “he’s not a he, Harriet, but a she. And she’s a fine layer.”

That left only Lucinda and Phoebe, his irresistible, naughty twelve-year-old twins. And there was only one couple who might – might – be able to help him rein them in when they debuted. Given that they were both exquisite and wild, even at the tender age of twelve, he shuddered to think of that event.

The Duke of Fletcher was the most elegantly dressed man in the anti-room he and his wife Poppy were also currently the most powerful couple in the ton. Put those two facts together with the fact that they were both extraordinarily beautiful, without being in the least vain, and they were the perfect couple to help usher the twins through their first year in society.

Phoebe and Lucinda didn’t wait to be formally introduced to their godparents, naturally. He fetched them from their mother and escorted them half way across the room, when Lucinda dashed the last few steps, threw her arms around Poppy and shrieked, “Isn’t it marvelous? You’re to be my new godmother! I hope you have a magic wand with you. Papa has been awfully mean about new bonnets lately.”

Not to be left behind, Phoebe ended up in Poppy’s other arm, although she instantly started an argument with her sister about magic wands and godmothers versus stepmothers.

Poppy looked up at Leopold, laughing, but it was Fletch who said it. “Couldn’t you have made us the godparents of that sleeping infant over there? I can only imagine the havoc these two are going to create in Almack’s.” Phoebe and Lucinda were spitting images of each other, with huge violet eyes and delicate faces that belied their reckless personalities.

“It’s Lucinda who terrifies me,” Poppy said, giving her a special squeeze.

“I’m sure they would never get into Almack’s given the fact they’re both complete hoydens,” Leopold said, “so I’m counting on Almack’s newest patroness to pull some strings.”

Poppy laughed, and Leopold turned around, looking for his wife.

There she was, waving at him. A group of clerics were clustered around the bishop, holding candles and incense dispensers, ready to bound up the aisle. Even through the stone walls of the Cathedral he could hear the excited babble from the chapel. It seemed that most of London had decided to attend the christening of the Duke of Villiers’s children.

The ceremony was formal…and not formal. Tobias walked up the aisle first, looking like an exact replica of Leopold himself. The Archbishop christened him, Jemma and Elijah vowed to renounce the vain pomp and glory of the world, and teach the same to Tobias – and Eleanor and Leopold enveloped him in a hug. The audience broke into happy exclamations.

And so it went, until the very last little Villiers, baby Theodore. Since Eleanor and Villiers were already at the top of the aisle, the future Duke of Villiers was not carried into church by his mother. Instead, his godfather carried him up the aisle.

The baby was wearing a christening gown sewn in the 15th century for the very first Villiers heir: the silk was so delicate that it tore if one looked askance at it, sewn with pearls and hanging all the way to the ground.

Tobias, Leopold’s first son, paced up the aisle holding the baby with a smile so proud that Leopold had to swallow hard so as not to disgrace himself. For his part, Theodore comported himself with ducal dignity, snoring quietly all the way up the aisle and waking only with the unwelcome touch of cold water.

Whereupon he broke into a howl that echoed off the arched roof of the cathedral. But by then Tobias had vowed to be a surety for his small brother, and Eleanor had cried, and all the children had gathered together, children and godparents, and parents, and they all ended up laughing rather than crying.

And even Theodore, after a measured look up at his big brother and godfather, consented to stop howling.

After all, he was surrounded by his family, and there was nowhere that he – or his father – felt more happy.

What happens to the orphans in A Duke of Her Own? Who fed them and took care of them after Eleanor and Leo left the orphanage?

I spread little updates about the orphans throughout the scenes following the orphanage chapter.

“How are the orphans doing now?” Villiers asked, breaking into the cool little silence that followed Lisette’s speech…

“Oh, very well!” Lisette replied. “The baker’s wife from the village has moved in temporarily. The committee is going to hire a new director.”

By the treasure hunt, the orphans are already much happier (and better fed), and the ladies’ orphanage committee has gathered:

The lawn was already dotted with the white gowns of the orphanage ladies, their lacy parasols making them look like daisies, viewed from above. The orphans in their blue pinafores were darting and running about and Eleanor didn’t think it was her imagination that they already looked heartier.

Finally, I wanted to remove the orphanage from Lisette’s neighborhood altogether, so later Eleanor is found writing a letter:

Eleanor looked up from a note she was writing to Lisette, commiserating over the fact the orphanage was being moved to another county entirely, when Villiers entered the room and closed the door behind him.

I assure you that the orphans were very well cared for, and that Eleanor and Leo never forgot about them. Indeed, they watched over that particular set of orphans throughout their lives, because without those orphans they would never have found the twins, nor—arguably—each other…

Why isn’t there a chess game in A Duke of Her Own?

The reason there’s no chess in the book has to do with Villiers’s own development: He started out the series completely obsessed by chess, and using the game as a substitute for intimacy and sex (thus the chess games with Jemma). He fell in love with Jemma through chess; we could even say because of her chess ability. Therefore, it was important that in the process of the books he move away from that substitution of chess for life, and toward an understanding of how important intimacy and love is. He got a fever and nearly died; he had a break from playing; and then there’s the signal game with Jemma when he doesn’t even care if he wins (she can’t believe it). That’s the turning point for Villiers: when he’s more absorbed in his children than playing a chess game. That’s why I couldn’t put a chess/sex game in his own novel: because he had to fall in love with Eleanor without a whiff of chess around. At the end I made it clear that she could play, just so they could have fun in the future… but their relationship had nothing to do with that sort of winning & losing.

And if you’re a fan of Villiers, you’ll be happy to know that he appears in all six of the original Desperate Duchesses books and the three By the Numbers books.

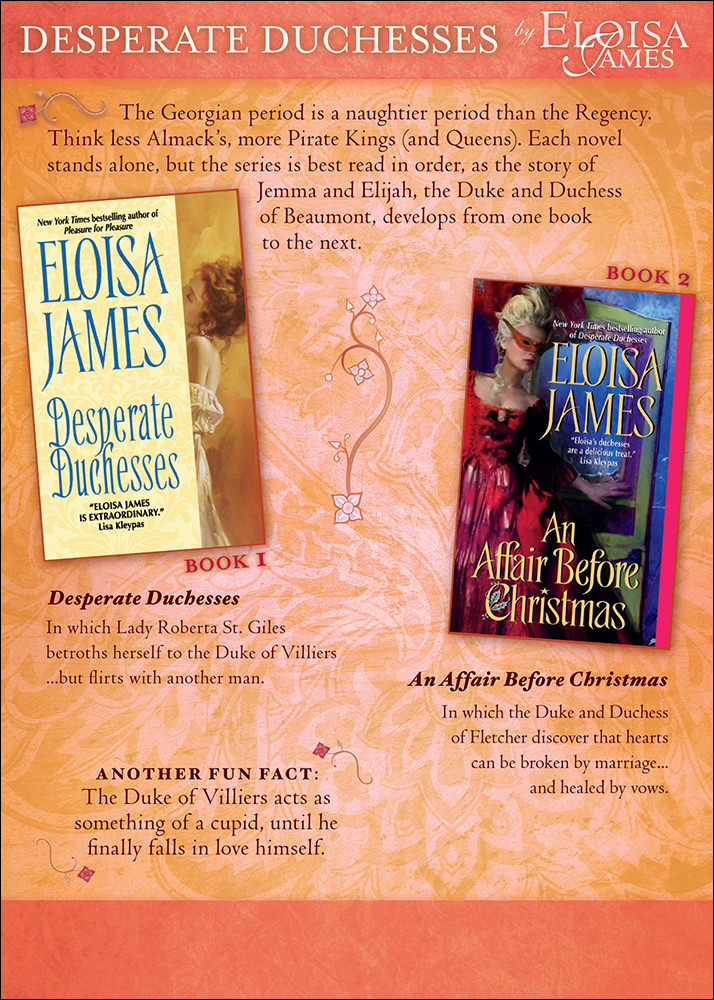

Desperate Duchesses (the Original Six) Collectible Card

The covers of each of Eloisa’s series are grouped together into gorgeous collectible cards. In addition to this card for the Desperate Duchesses (the Original Six), there is a card for the Duchess Quartet, Eloisa’s Fairy Tales and the Essex Sisters.

Note: Collectible cards are no longer available.

A Multi-Author, Mini-Poster of Bookmarks (Download)

Enjoy these gorgeous downloadable bookmarks featuring titles from Julia Quinn, Laura Lee Guhrke and Elizabeth Boyle! Click to download, cut them out and share them, or leave the pdf whole as a collectors’ item.

Her Own: NYT Bestseller

New York Times Bestseller List at #13!

Her Own: The Season

Readers’ Choice for favorite historical, August 2009, The Season

Her Own: Amazon Romance

Named one of Amazon’s Top Ten Romance books of 2009