Bookcode: desperate

desperate: Audible Top 50 Romance Essentials

Audible has included Desperate Duchesses in their Top 50 Romance Essentials!

Extra Chapter for Desperate Duchesses

Chapter Three

From Damon’s Point of View

There are days that one cares to remember months later, and there are days that one would just as soon have stricken from the book of life. Or whatever that tome was really called. Damon had always thought that instead of a recording angel somewhere, totting up lists of crimes for future punishments, the fellow was likely handing out the punishments right on the spot. To wit:

Damon Reeve, Earl of Gryffyn. April 8, Slothful to the bone, didn’t rise from bed til noon

Punishment for said Deadly Sin: April 10, hellish conversation with brother-in-law

“Did it occur to you that the presence of an illegitimate child in my house is not precisely helpful to my career?” bellowed said brother-in-law.

Damon had to admit Beaumont had a point. The House of Lords was a dashed stuffy lot. Without a doubt, most of them probably threw any children foolish enough to born out of wedlock out the door. In fact, he would quite like to do that himself. It would make life much easier. It was just that somehow Teddy …

He shrugged. He wasn’t one of those happy fellows who could send Teddy off to live in a sheep farm somewhere in the country simply because the boy was unlucky enough to be born out of wedlock. Or unlucky enough to have him for a father, however you wanted to look at it.

Naturally his sister Jemma had leapt to his defense and was battling it out with her husband.

Beaumont made a comment about Jemma’s reputation, and she snapped back something about him bleating about his career. Damon winced at that one. To call a man who worked as hard as Beaumont did a bleater seemed a bit stiff. Her brother-in-law gave her a homicidal glare and then stalked off.

Jemma’s face was red as fire, just the way she used to look when they were children squabbling over a toy. Really, the more he saw of his sister’s marriage, the more Damon was happy to think that he himself had escaped matrimony.

“You see why I wanted you to move in with me, Damon?” Jemma said, with a catch in her voice. “I can’t do it, I really can’t. I can’t live here with him.”

Damon was all sympathy, but after all, she was married to the man. “I’ll come for a visit if you really want me to, Jemma, but I think it would be easier for both of you if I didn’t.” Not to mention, he added silently, easier for myself.

“I shan’t survive here otherwise, Damon. I can’t live with Beaumont.”

Jemma kept babbling on about her inability to live with her husband – something that was no surprise to Damon, given as she’d spent the last eight years in Paris, living as far away from the said spouse as possible – when Damon suddenly noticed that the little charity worker, who had turned out to be Lady Roberta someone-or-other, was watching the whole thing from the side of the room. As soon as he met her eyes, she vanished back into the sitting room.

Perhaps she’d gone off to have a good fainting spell. Though that depended whether she was from the Reeve side of the family (which included Jemma and Damon, and their propensity for scandal), or the Beaumont side of the family (righteous in every way and bound to go straight to the top of the line at the pearly gates).

Lady Roberta didn’t look like a shoe-in for the pearly gates. Not with that red hair, and those gorgeous eyes. They tilted at the corner, like the eyes of a Venetian courtesan. Though few courtesan had lips that color without painting it on, and he didn’t think that the country relative had been near a pot of lip color.

Jemma followed Lady Roberta into the sitting room, so Damon went as well. After all, any relative of Jemma’s was bound to be one of his. It was his duty to make her comfortable. No one could say that he wasn’t a family man, not given his inappropriate fathering of Teddy.

He barely got in the room before Jemma snatched away the plate of ratafia cakes, started trying to get him to leave, and generally acting like the shrewish little sister that she was.

“I haven’t even met Lady Roberta properly,” Damon pointed out.

“This is Damon Reeve, the Earl of Gryffyn,” Jemma said, with an irritating sigh. “If I tell you that his best friends call him Demon, you’ll know precisely how unworthy he is. Beaumont was absolutely right about his laziness: he never does a worthy action all day.”

“A charming introduction,” Damon said. “Please call me Damon. After all, we’re family members, as I understand.” He took another cake and eyed the cousin under his eyelashes. He’d never seen quite such an ugly dress in his life, but her figure…that was another story.

Naturally Jemma took the plate away and put it on the floor between herself and Roberta, so he couldn’t eat any more. And then he and Jemma bickered a bit about whether he ought to accept her invitation to stay in the house. But in truth, Damon had made up his mind to stay in his own house. Why on earth would he move across town to Beaumont’s townhouse, when it would just cause aggravation to his brother-in-law? It wouldn’t make it any easier for Jemma to live with her husband, and likely worse. Jemma was turning him into one of the many weapons she wielded against her husband.

“I hardly want to cause the fraying of your marriage,” he pointed out.

Jemma snorted inelegantly. She sounded just like their former governess, a fact that he stored away to infuriate her with some day.

“Beaumont doesn’t mean to be such an ass,” Damon added. Really, if you looked past the melon-colored bodice, Lady Roberta seemed to have a delectable chest.

“He just acts that way?” Jemma with a bitter little twist to her voice. “But enough airing our linen, dirty and otherwise, in front of Roberta. You must bring Teddy and his nanny this very afternoon.” More and more like their governess. Any moment she’d be ordered him to pay a visit to the chamberpot.

“Unfortunately, he has no nanny at the moment,” Damon said, deciding to distract her. “Teddy has an annoying habit of escape and the latest nanny stomped away in a temper yesterday.”

“Escape? Where does he go?”

“Anywhere but the nursery. Generally he goes to the stables during the day. And he wanders the house at night until he finds my chamber, and then he climbs in my bed.” He stole a look at Roberta. She hadn’t said much yet, but ladies always loved pathetic stories about little children. They couldn’t help it. “Last night,” he added sadly, “Teddy couldn’t find my bedchamber, so he slept in the vestibule until I came home. Marble floor. Cold, I should think.”

“My father had a dog like that,” Lady Roberta said. And then she clapped a hand over her mouth. “I didn’t mean to compare your son to a dog, my lord!”

Damon bit back a grin. So much for sentimental gush about babies. She had to be from the Reeve side of the family tree: that dry irony was a family trait. “You really must call me Damon,” he told her. “Children are slightly doggish, don’t you think? They need so much training, and they have a dislikable habit of urinating in public places.”

“I suggest you bar the nursery door,” Jemma said coolly, “particularly now that you remind me of children’s indiscriminate attitude toward hygiene.” Obviously his beloved sister was rethinking the whole living-with-her-darling-nephew idea.

“Can’t do that,” Damon said. “What if there was a fire? And Teddy, by the way, is past the age of indiscriminate peeing. He’s very good at seeking out a tree, just like the well-trained puppy he is.”

“Perhaps you could carpet the vestibule,” Roberta suggested. “If you mean to allow him to continue in this habit.”

Damon couldn’t help grinning at her. She was a sharp tongued little thing. Like a sweet with a bite in the middle. His favorite.

“That’s remarkably uncharitable of both of you,” he said, throwing Roberta his very best flirting smile, the one that said I like you, and a load of other things besides. Then he did a double-take. Roberta met his smile with a funny, ironic little one of her own – a smile that he’d seen a million times on his sister’s face. Damned if she wasn’t some sort of illegitimate daughter of his father.

“How odd!” he said, wondering if the recording angel had noticed a bout of incestuous lust, or whether it didn’t count if the sinner didn’t know that the lady was his sister. “I suddenly see quite a resemblance between the two of you. I have it — my illegitimate child is only matched by our father’s own indiscretions!”

“Actually not,” Roberta said.

Damon felt a grin curl his lips. He was ridiculously pleased to hear that.

“I’m legitimate, but from a far branch of the family tree. I only wish that I resembled Jemma.”

Far branch, eh? He was alarmingly pleased. “You have Jemma’s blue eyes,” he said. Her eyes were more beautiful than his sister’s, but he wasn’t going to say that aloud. Jemma had boxed his ears for less when they were children.

What he really wanted to know was just how far out on the family tree her particular branch was located.

“Roberta is going to be my project,” Jemma said. “I’m going to dress her up to look absolutely gorgeous, which of course she is, and then marry her off to whomever she wishes. It’ll be great fun.”

It did sound like fun. Damon wouldn’t mind dressing up – or down – Roberta himself. In fact, why bother with dressing at all?

Roberta seemed to be a little worried about money, but if there was one thing the Reeves didn’t have to worry about, it was money. Jemma’s husband had loads, and he himself had even more.

“Jemma’s husband can manage a dozen debuts and not notice,” he told her. “I don’t know why Beaumont bothers with his speechifying; he could just buy the votes he needs to get a bill passed, in the time-honored fashion. That’s what father always did.”

“I’m afraid that the third earl – our father – was a tad disreputable,” Jemma said. “You interrupted me, Damon. I was trying to warn Roberta that she might not want my chaperonage.”

Of course, no young lady in her right mind would choose Jemma as a chaperone. His sister was only married a couple of weeks before she scandalized all of London by haring off to Paris. Much though he loved his sister – and he did, for all her snappiness – Jemma was no model of ladylike behavior. But then… he looked Roberta over.

She didn’t look like a model of virtue either. There was just something about her. No question she was a virgin. But she was the least virgin-like virgin he’d ever seen, with that ruby red lip. And the way her eyes…not to mention the fact that she looked like a delicious peach. He’d—

Roberta was turning pink and Damon was damn sure that she knew exactly what he was thinking. He pulled himself together and reminded himself of his code of ethics. No innocents.

But if she chose to stay with Jemma, then she wasn’t entirely off-limits. If she left the house with a shriek of dismay, then – then she was innocent by definition.

“It’s true that your reputation is marred by merely walking into this den of inequity,” he said bluntly. “Or it will be once the English ladies get the measure of my sister. My sister is unlikely to be a prudent chaperone. The Reeves have been disreputable back to the days of King Alfred, and though I regret to say it, the tendency bred true in both of us.”

She didn’t look very shocked.

“Jemma has neglected to tell you that I am the only child of the Mad Marquess, to use the term the popular press prefers,” Roberta said. “So the ton will have more hurdles than Jemma’s reputation to consider when it comes to my marriage.”

Damon’s mouth fell open. Roberta was the daughter of the Mad Marquess – ie, the marquess who lived with a succession of mistresses, if even half the stories were true. Meaning that she had grown up with a succession of mistresses at the dining room table. Not innocent. No.

He could feel a wolfish kind of smile on his lips. “You grow more fascinating by the moment,” he murmured. “Do tell me a bit of poetry.”

She ignored him, and handed Jemma one of her father’s poems, which was just as incomprehensible as he would have expected.

Jemma, being a really decent person at the heart, kept rereading the poem and trying to get her mind around it. “But what’s the part about a rude ungrateful bear, enough to make a parson swear?” she finally asked, looking up from the sheet of parchment.

“I find with Papa’s poems that it’s best not to devote oneself too strictly to meaning,” Roberta said. Her voice had just the right hint of dry amusement: loving to her father, and yet aware.

Damon let out a bark of laughter. She was a Reeve all right. He’d never met a woman as smart as Jemma – until now.

He wasn’t moving into the house to stay with Jemma. But damned if he wouldn’t be over every day, just for the pleasure of talking to a woman with a sense of humor.

“There is just one more thing that I should tell you,” Roberta said.

“Wait, don’t tell us,” Damon said. He was feeling foolishly happy, for no good reason. “The family character bred true in you as well, remote relative though you are. Let’s guess: You have a child – you, with such a young, innocent –”

“No!” Roberta said, frowning at him.

But before she could continue, he said: “Your turn, Jemma.”

Jemma looked thoughtful. “At some time last year, you were in an inn. You gazed out of the window and were instantly struck by an ungovernable passion for my brother.”

“Very nice!” Damon said. “But can you work Teddy into the picture?”

“More than anything, Roberta wished to be a mother, but unfortunate circumstances have decreed that she will have no children of her own, therefore Teddy will become her most cherished possession.”

“What about me?” Damon said, laughing. “I want to be her most cherished possession.” He shocked himself and almost choked.

Jemma turned to Roberta. “You must forgive us; it’s an old game that we –” She stopped. “You did see Damon last summer! And you fell in love with him? How very peculiar. Are you sure you wish to marry my brother? I can assure you that he’s terribly annoying.”

Roberta started giggling. “No, I don’t wish to marry your brother!”

“There’s no need to be quite so emphatic,” Damon said, raising an eyebrow. “I would quite like to marry you myself, although I see that I shall have to assuage my grieved heart elsewhere.”

She was laughing at him, this new cousin of his.

It wasn’t even a decision, really. Of course he would move into the house for a few days to succor his newly-returned sister.

Nothing to do with his new cousin.

Extra Chapter for Desperate Duchesses Series

May 1791 (a short time before the Epilogue of A Duke of Her Own)

The London residence of the Duke of Villiers

15, Piccadilly

Everyone in the house – about fifty-eight souls – knew the Duchess of Villiers was in labor; mortifying though it was, Eleanor was perfectly aware of the public status of her condition.

The fact could hardly be kept private when one’s water breaks unexpectedly in the breakfast room. One minute Eleanor was greeting their butler, Ashmole, good morning, and the next she was surrounded by an unpleasantly warm puddle of water.

Ashmole’s face didn’t even twitch. His eyes followed her astonished gaze to the floor, his head snapped up, and he began dispatching footmen in all directions: to the accoucheur, midwife, Eleanor’s maid, her sister, her —

“Not my mother,” Eleanor interrupted. She knew she had turned rather pink, but she picked up her skirts and sailed – not an inappropriate metaphor under the circumstances – up the stairs without meeting the eyes of any of those footmen, nor her butler, nor her husband.

She couldn’t have done the last anyway, as the duke was behind her, pushing her up the stairs as fast as he could, apparently worried that the babe would plop onto the floor.

At the top of the stairs, Leopold rushed before her, the better to tow her through the door (ho ho) and deposit her on the bed.

“Lie still,” he commanded, turning to pull the bell so fiercely that the cord snapped off in his hand.

She took advantage of his startled curse to roll off the other side of the bed.

“You shouldn’t be standing up!” he said, heading toward her as if he intended to pin her onto the bed.

But Eleanor, who was inexperienced rather than unintelligent, had just realized that the nasty backache that had kept her awake all night was not merely an ache. In fact, it couldn’t be catalogued under that word at all; it was rapidly turning into something quite different, more along the lines of an encounter with boiling oil.

She reached out just in time, grabbed the bedpost and managed to say, “Don’t touch me,” between clenched teeth.

Leopold froze.

“All right,” she panted, a moment later. When he didn’t answer immediately, she realized that her beloved husband had turned quite…well, white wasn’t the right word. More greenish. With an interesting purple tint under his eyes. You’d think he was the sleepless one, whereas she knew for a fact that he’d slept like the proverbial baby since she had been awake to catalog the passing hours.

“You’re in pain,” he said, showing a level of intelligence that she could only hope would be surpassed in their offspring.

“I don’t want a crowd of people in here, Leopold,” she told him. “I’m not the queen.” Poor Queen Charlotte delivered all her babies before a crowd, a fact Eleanor had absorbed with horror. “And keep that accoucheur out; he’s a pompous idiot.”

At that very moment the door opened and a tidal wave of women poured into the room.

“I can’t –“ Eleanor gasped, realizing that there was another bout of pain starting at her toes. Or it would be accurate to say that it started at her thighs and swept upwards.

She turned to the only person whose face she could see clearly, grabbed the bedpost again and told him with a ferocity that female royalty would certainly envy, “Get them out of here!”

“All but the midwife,” Leopold bargained. His eyes looked rather wild. “If not the accoucheur, the midwife. She probably needs to…look at you or something.”

Eleanor gripped the bedpost so hard that she was surprised it didn’t splinter. “I’m not the queen,” she said, not making much sense but they both knew what she meant.

The life of a duchess is lived in public. Eleanor knew that and accepted it. Most of the time, she quite liked it. What woman in her right mind wouldn’t enjoy the cheerful company of a houseful of people bent on pleasing her?

But this was different. The pain made Eleanor feel like mooing like a cow and she intended to do that alone.

“Get them out,” she said, hissing it like a teakettle about to explode.

When the contraction was over, Leopold eased her back on the bed. “Just let the midwife examine you for a moment,” he pleaded. “I promise that they’ll leave you alone. Look, the wet nurse is gone, and the maids too.”

She caught her breath, hardly listening as Leopold informed the midwife that no, he wasn’t leaving until his wife asked him to, and then informed the woman she had exactly one minute to make her examination because, he said, “The duchess wants you out of the room.”

If there was one thing the Duke of Villiers was excellent at (and privately, Eleanor thought there were quite a few), it was terrifying the unwary into compliance. It took a few minutes, and another contraction, but the protesting midwife found herself on the opposite side of the door.

Eleanor managed to pull herself upright again. It felt better that way. She hung onto the bedpost through another contraction.

“Walk,” she gasped, once she had control of her lungs again.

“Where?”

She pushed Leopold out of the way. If he wouldn’t help her, she’d walk on her own. She’d never felt like this before: in the grip of something bigger than herself.

“Where are the children?” she croaked.

“You had them sent to the country two days ago,” Leopold said. “Don’t you remember? Eleanor, are you sure –“

He was grabbing at her again, so she swatted him off. “I’m going to walk.” With that she made her way, like a rather large and over-burdened tugboat, around the end of the bed. She opened the door to find a perfect wilderness of women hovering in the hallway.

From behind her she heard one word from her husband, a word which distilled years, nay centuries, of dukedom into one command: “Out!”

They fled.

The picture gallery, Eleanor decided. It was long and quiet.

Leopold was walking backwards before her. “Darling, where are you going?” he said, calmly enough, given that his hands were visibly shaking.

“The gallery,” Eleanor managed, but then she had to stop and hang onto him. She felt as if she were in a huge storm at sea, and he were the mast.

Two hours later, they were making their fortieth turn down the gallery when she realized that the storm was entirely Leopold’s fault. She told him that, between contractions.

“You’re right,” he said soothingly.

“Don’t talk to me as if I were an old woman in need of lies! You sound like a monkey’s arse!” It was the rudest phrase she could come up with. “I’m never doing this again. Never. Don’t say a word to me… Owww!”

When the pain stopped wrenching its way down her legs, she realized that she had actually ripped the shoulder off from Leopold’s linen shirt. “You shouldn’t wear such fine clothes. Not when –“

She broke off. “I think we need the midwife now.”

“Not here,” Leopold said between clenched teeth. He swept her into his arms.

“Don’t drop me!” Eleanor squeaked.

“Never,” he said, carefully walking the length of the gallery. He maneuvered her through the door, down the corridor, and back into her bedchamber. He stuck his head back out the door for a second to bellow “Mrs. Bannockburn!”

“Hell’s bells,” Eleanor gasped. She felt like arching her back, so she did that.

The midwife tumbled in the door, saying something idiotic about the baby not being likely for hours yet.

“It’s already been hours. She’s coming now,” Eleanor snarled. She could feel a sweaty lock of hair sticking to her forehead.

“New mothers!” Mrs. Bannockburn said, clucking. “Always think they know what’s what…babies take their own time.”

“Wash your hands before you touch my wife,” Leopold snapped.

Mrs. Bannockburn turned a little ruddy. “I always wash my hands. Now I’ll just have a peek and see whether we’ve made any progress.”

“You haven’t made any,” Eleanor growled. “But I’ve made a lot.”

One quick look under Eleanor’s chemise and Mrs. Bannockburn’s face changed.

“We’re about to have a baby here, Your Grace,” she told the duke, deftly snatching towels from a waiting stack and tucking them under Eleanor’s bottom. “May I request that Your Grace leave the room now? This is a matter for women.”

“Out!” Eleanor managed with something of an echo of Leopold’s own command.

He leaned down and took her face in his hands. “I don’t deserve to be anywhere near you, darling. I’ve never seen such courage.”

She managed a smile and then he was gone. Eleanor arched her back again. “I have to –“

From the corner of her eye she saw Mrs. Bannockburn push her husband from the room.

Then the midwife was back, her voice suddenly soothing. “I see a bonny little head, Your Grace,” she said. “I want you to focus on me. See me? Do you see me?”

Authority had moved from Leopold, to Eleanor, to Mrs. Bannockburn. The midwife was unquestionably in charge.

Eleanor managed some sort of gasp in reply.

“Wait for it,” Mrs. Bannockburn said. “Wait…wait…now. Push, Your Grace. Push like you’ve never pushed before.”

I’ve never… Eleanor thought, but lost the words. I’ve never…

Some time later she still hadn’t finished the thought, but she was staring down at ruddy, bald head. “I’ve never seen such an ugly baby,” she said suddenly.

“Oh tush,” Mrs. Bannockburn said. “I’ve seen much worse. Besides, it wouldn’t be fair to all the other babies born today if he were handsome. He’ll be a duke and that’ll get him a woman in his bed if he turns out as skinny as a rooster.”

“Leopold has to see him,” Eleanor said, touching the baby’s blotchy cheek. “This nose is his fault. And his lip? What happened to his upper lip? There’s no one in my family who has such a thin mouth. Why doesn’t he open his eyes?”

“Don’t worry about that. He’s a bit tired, but he’s breathing nicely. Babies tend to look like that. He’ll have a lovely little mouth, you’ll see. Let me just clean up a trifle more and bring in your maid, and then we’ll have His Grace in to see his son.”

Eleanor stared down at the child. She’d been so certain she was carrying a girl. But instead she had been totting around a plump bald boy with a nose that resembled nothing so much as a potato. As she watched he finally opened his eyes.

They were the color of cornflowers. He peered at her, rather puzzled…

“Hello,” she said. Something twanged in the area of her heart.

There was a whisper of motion next to her and she looked up to see Leopold, his hair fallen from his ribbon and his shirt still ripped at the shoulder. He was staring down at the child and suddenly she knew exactly where that nose had come from.

She started laughing. “He’s going to look just like you, Leopold.”

“I feel as if I should apologize to him already,” Leopold said. “Though I assure you that my head is quite flat on top. He’ll have to go to Almack’s in a stocking cap to cover it up that pointed bit.”

Mrs. Bannockburn laughed. “It’ll sort itself out,” she said. “Now Your Grace, I’ll ask you to take the babe outside for a moment or two while Her Grace and I finish up.”

“No,” Eleanor said, her arms tightening. “I don’t want to let him go yet.”

“And I don’t want to hold him,” Leopold said, backing off. “He’s absurdly small.”

“I’m sorry, Your Grace,” Mrs. Bannockburn said to Eleanor, “but I need your attention. I’ll call the wet-nurse, shall I?”

“I’m nursing him myself,” Eleanor said, making up her mind that very moment. For the baby was still looking at her. And while he would never, ever be beautiful, he was somehow…beautiful.

“I’m going to have to buy him a wife,” Leopold said, echoing her thought. “He’ll never find one on his own.”

“He can live with us forever,” Eleanor said. “Look at his sweet little cheeks, Leopold. And he has the most darling fingers. Just look how they curled around my finger. I think he’s very, very bright.”

“It would be handy,” Leopold said, still looking at the baby. “Have you looked over the rest of him? Are all his male parts in order?”

She couldn’t help a little grin. “They’re as big as his nose. Bigger!”

“Your Grace,” Mrs. Bannockburn said patiently.

“You take him, Leopold,” Eleanor said. “I don’t want anyone else touching him yet. Just the two of us.” She watched him carry the baby out the door as gingerly as if he were carrying a crystal egg.

A half-hour later Mrs. Bannockburn allowed that she could have the baby back. When Leopold came in, Eleanor was sitting up, feeling exhausted but clean, in a snowy white chemise.

There was something different about Leopold’s face when he walked in: something fierce, and proud. “Look at this,” he said, sitting down on the edge of the bed but not giving the baby back. “He’s opening his mouth like a little fish. He’s going to be talking soon.” He beamed down at him.

Eleanor couldn’t help it; the joy welled up in her heart until she started laughing and couldn’t stop.

“I sent for the children,” Leopold said. “They’ll love this. Look, he’s opening his mouth again, just like a little doll.”

“He’s – “ But a sudden bellow from the little doll interrupted Mrs. Bannockburn’s comment.

“Hungry,” she continued.

The christening of Theodore, future Duke of Villiers, took place a few weeks later. By then Leopold and Eleanor had grown accustomed to less sleep and more joy. Leopold spent most of his time arranging for the baptism; Eleanor spent most of hers trying to keep her insatiable son fed.

She was lolling in bed the day before the baptism when he came in to enumerate the final details. “They’ll all be baptized one after another,” he told her, “except for the twins who insist on being baptized together. So the Bishop and the Dean will step forward and do them at the same time.”

Theodore burped loudly.

“I’ll have to rely on Ashmole to keep the godparents in proper order in the back of the cathedral. I’m afraid there’s going to be a lot of people. I just hope we made the right decision by making the ceremony public.”

“We knew people would be interested,” Eleanor said sleepily. “It’s not often that a duke decides to baptize all of his children at once.”

“Well, I can’t be sure the others were baptized,” he told her, once again. “How could I baptize Theodore if I might have missed one of the others? Besides the Bishop assures me that too much baptismal water is better than too little.”

Leopold paused for a moment, staring down at the baby. “Remember how ugly he was at first?”

Theodore was sleeping, his mouth pursed like a plump, beautiful rosebud. His head was perfectly round, and even his nose seemed to have diminished a bit. “He was never ugly,” Eleanor said, and then started to laugh. “Well, perhaps he was.”

The christening was a very grand affair. Leopold had decided that everything to do with his illegitimate children would be conducted with the utmost pomp and ceremony, thereby ensuring that the ton realized that the full weight of his power lay behind each and every child. They were dressed like little princes and princesses, all the way from Tobias to the twins.

The Duke and Duchess of Beaumont were the first to arrive, sweeping into the anti-room with the kind of air of splendor and excitement that always accompanied them. Not to mention the squeals of their own children, who pounced on their favorite play mates.

“Stay off, you little monster,” Jemma called to her eldest child. “Evan! Can’t you see that Lucinda is far too elegant for such rough play? For goodness sake, Villiers. Do you have that child in cloth of gold?”

“They all are,” Villiers said imperturbably. He himself was dressed with wild magnificence, in black velvet embroidered with pearls.

“Tell me again,” Elijah said. “Just who am I godfathering?”

“You have Tobias,” Leopold said, pulling his eldest son to his side. “He needs you the most because he’s the most wicked. And you –“ he gave Elijah a lopsided smile, “—are such a sanctimonious type that I’m hopeful you’ll rub off on him.”

At twenty, Tobias was at Oxford along with his brother Colin, and though he still had the lean figure of a very young man, he was as naturally graceful and dignified as someone much older. The product of his upbringing, Leopold and Eleanor told each other.

Leopold left Tobias with Elijah and Jemma, and caught Violet. She was quietly watching the children racing around the room, a sweet little smile on her face. She was the child he worried about the most, he thought, because she would never demand what she most needed.

He reached out and plucked the Duke and Duchess of Cosway from the midst of the hoards of children now crowding the vestry. “You two,” he said, “will be godparents to Violet.”

Violet blushed with all the violence of a thirteen-year-old girl, and dropped a curtsy.

Isidore held out her hand, with that lavish, mischievous smile that won the hearts of all who knew her. “Darling Villiers, you’ve made me so happy. I’m absolutely outnumbered in our household,” she told Violet. “I have these two naughty scraps who happen to be male, and Lucia and I run around madly just trying to make ourselves heard.” She wrapped an arm around Violet. “Now whenever you’re with us, Lucia, you and I can range ourselves against Dante, Pietro and the duke, and we’ll win all the games.”

Simeon snorted. “Don’t count on it,” he told Violet. “The other week she smashed a cricket ball straight through one of the windows.”

Leopold watched Violet relaxing into the curve of Isidore’s arm and turned away with satisfaction.

He got hold of his second son, Colin, by dint of pulling him out from under a heap of little boys, most of whom were future dukes. Colin was eighteen and full of laughter; unlike Tobias, he was unmarked by his early childhood. In fact, he liked to tell romantic stories to the other children about his days as a weaver’s apprentice. Leopold marched him over to the Earl of Gryffyn and his lovely wife, Roberta.

Damon turned around with a grin. “That boy is going to be taller than you are, Villiers,” he said.

“This is your new godson,” Leopold said.

“Colin!” Damon said. “How are you doing at Christ Church?”

“The porters still point out your room to all the first years,” Colin said with an impudent twinkle that mirrored Damon’s.

“Famous, am I?” Damon said.

“Infamous, I’ve no doubt,” his beautiful wife Roberta put in.

Colin turned to her. “He put a turkey in the bed of the head of college. It was stuffed with dead fish, and then he let in three cats in the middle of the night.”

“Pooh,” Damon said. “That was just my first year, and it was five cats. Wait til I tell you what I did to the statue of Mercury that stands in Tom Quad.”

Leopold eased away. That was Tobias, Colin, Violet… Genevieve, Lucinda and Phoebe left. He found the girls easily enough, by locating his wife and the baby. He stood for a moment, watching them coo at the child.

Genevieve had grown up in the country, with her mother. Even after he located all of his missing children and brought them home, he never took her from her mother, although he bought them a snug little house and all the comforts they could wish.

And when Genevieve’s mother died a year later, it was very sad – but not tragic, because then Genevieve came to them for more than a holiday. In the beginning, she attached herself to Eleanor like a limpet, but in time she became the peacemaker, the child who stood between Violet’s and Lucinda’s most violent quarrels.

He brought her to Harriet and Jem Strange (also known as the Marquis and Marchioness of Broadham). Harriet greeted Genevieve with delight. “I haven’t seen you since Twelfth Night.”

“How is my chicken?” Genevieve said, smiling shyly.

“Hale and hearty,” Harriet said. “Peters would love to cook him for supper, but I’ve told him that after surviving the terror of being a prize at Bartholomew Fair your chicken deserves to live to old age.”

“Plus,” Jem said, joining them, “he’s not a he, Harriet, but a she. And she’s a fine layer.”

That left only Lucinda and Phoebe, his irresistible, naughty twelve-year-old twins. And there was only one couple who might – might – be able to help him rein them in when they debuted. Given that they were both exquisite and wild, even at the tender age of twelve, he shuddered to think of that event.

The Duke of Fletcher was the most elegantly dressed man in the anti-room he and his wife Poppy were also currently the most powerful couple in the ton. Put those two facts together with the fact that they were both extraordinarily beautiful, without being in the least vain, and they were the perfect couple to help usher the twins through their first year in society.

Phoebe and Lucinda didn’t wait to be formally introduced to their godparents, naturally. He fetched them from their mother and escorted them half way across the room, when Lucinda dashed the last few steps, threw her arms around Poppy and shrieked, “Isn’t it marvelous? You’re to be my new godmother! I hope you have a magic wand with you. Papa has been awfully mean about new bonnets lately.”

Not to be left behind, Phoebe ended up in Poppy’s other arm, although she instantly started an argument with her sister about magic wands and godmothers versus stepmothers.

Poppy looked up at Leopold, laughing, but it was Fletch who said it. “Couldn’t you have made us the godparents of that sleeping infant over there? I can only imagine the havoc these two are going to create in Almack’s.” Phoebe and Lucinda were spitting images of each other, with huge violet eyes and delicate faces that belied their reckless personalities.

“It’s Lucinda who terrifies me,” Poppy said, giving her a special squeeze.

“I’m sure they would never get into Almack’s given the fact they’re both complete hoydens,” Leopold said, “so I’m counting on Almack’s newest patroness to pull some strings.”

Poppy laughed, and Leopold turned around, looking for his wife.

There she was, waving at him. A group of clerics were clustered around the bishop, holding candles and incense dispensers, ready to bound up the aisle. Even through the stone walls of the Cathedral he could hear the excited babble from the chapel. It seemed that most of London had decided to attend the christening of the Duke of Villiers’s children.

The ceremony was formal…and not formal. Tobias walked up the aisle first, looking like an exact replica of Leopold himself. The Archbishop christened him, Jemma and Elijah vowed to renounce the vain pomp and glory of the world, and teach the same to Tobias – and Eleanor and Leopold enveloped him in a hug. The audience broke into happy exclamations.

And so it went, until the very last little Villiers, baby Theodore. Since Eleanor and Villiers were already at the top of the aisle, the future Duke of Villiers was not carried into church by his mother. Instead, his godfather carried him up the aisle.

The baby was wearing a christening gown sewn in the 15th century for the very first Villiers heir: the silk was so delicate that it tore if one looked askance at it, sewn with pearls and hanging all the way to the ground.

Tobias, Leopold’s first son, paced up the aisle holding the baby with a smile so proud that Leopold had to swallow hard so as not to disgrace himself. For his part, Theodore comported himself with ducal dignity, snoring quietly all the way up the aisle and waking only with the unwelcome touch of cold water.

Whereupon he broke into a howl that echoed off the arched roof of the cathedral. But by then Tobias had vowed to be a surety for his small brother, and Eleanor had cried, and all the children had gathered together, children and godparents, and parents, and they all ended up laughing rather than crying.

And even Theodore, after a measured look up at his big brother and godfather, consented to stop howling.

After all, he was surrounded by his family, and there was nowhere that he – or his father – felt more happy.

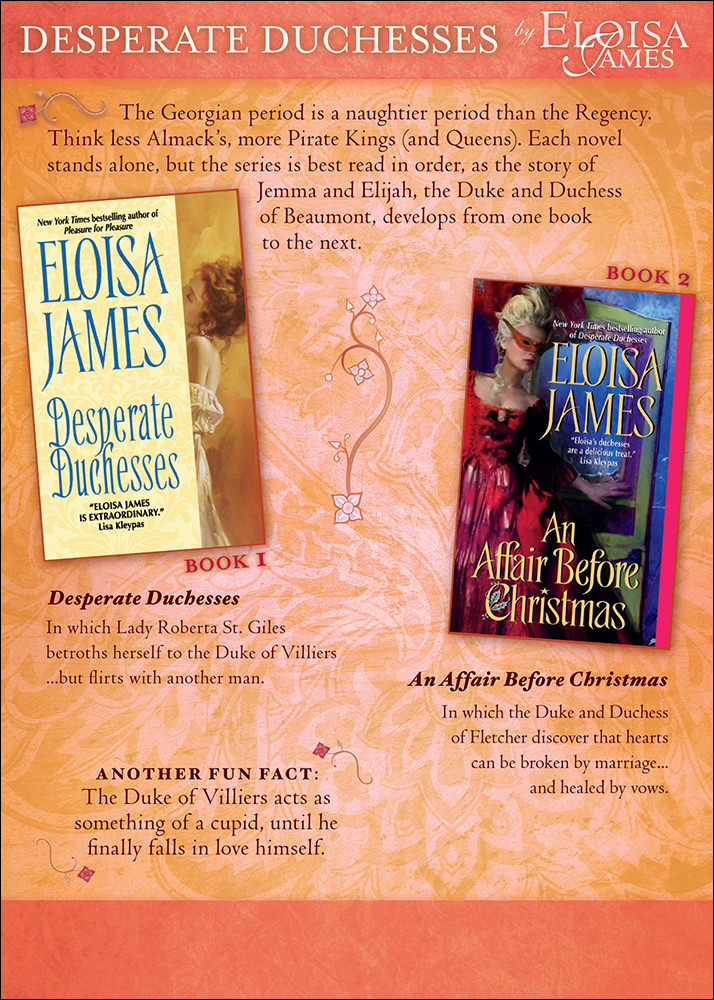

Desperate Duchesses (the Original Six) Collectible Card

The covers of each of Eloisa’s series are grouped together into gorgeous collectible cards. In addition to this card for the Desperate Duchesses (the Original Six), there is a card for the Duchess Quartet, Eloisa’s Fairy Tales and the Essex Sisters.

Note: Collectible cards are no longer available.

Desperate: USA Today Bestseller

#27 on the USA Today Bestseller List

Desperate: NYT Bestseller

Tied for #15 on the New York Times Bestseller List

Desperate: Publishers Weekly Bestseller

#5 on Publishers Weekly Bestseller List

Inside Desperate Duchesses

- I dedicated this book to my father, Robert Bly, winner of the National Book Award for Poetry. Least you think that I am the only one in the family writing of love, here’s a snippet of one of my father’s love poems, taken from Loving a Woman in Two Worlds (1985):

I want to be the man

And I am who will love you

When your hair is white.

- I also dedicated this book to Christopher Smart, whose poems I ruthlessly chopped and used for the Mad Marquess’s verse. Christopher Smart was slightly crazy – but not a truly bad poet. My favorite poem of his is called “For My Cat, Jeoffry”. Here’s a link to the whole poem. I love my cat Rosie, and Smart’s poem captures her:

For there is nothing sweeter than his peace when at rest.

For there is nothing brisker than his life when in motion.

- There’s a Shakespeare echo on page 36. Roberta says to be a duchess is consummation devoutly to be wished, but then she can’t remember where the quote came from. It’s from Hamlet in “To Be Or Not to Be” talking about death… a bleaker thing to wish for than Roberta’s comment about the title of duchess.

- Part of Roberta and Villiers’s conversation circles around a Shakespeare poem, The Rape of Lucrece. This is not a cheerful poem, and I don’t really recommend it for light reading. But if you’d like to dip in, here’s a link to the whole text.

- Damon makes fun of one of my favorite love poems on page 163: Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to his Love.” Marlowe doesn’t talk of parsnips but of making beds of roses for his beloved. Here’s the whole poem, for your pleasure.

- Want to know Damon’s point of view? Read the extra chapter three of Desperate Duchesses to find out!

- When I first designed the plot of Desperate Duchesses , I thought I would detail the chess games on the website. But you know…chess is complicated to follow and my guess is that few chess masters are going to check eloisajames.com to see whether I correctly notated the Center Game played in Leipzig in 1903 (which was Jemma and Villiers’ first match). So let me assure you that every game I describe was a true game, played between masters, as notated in a wonderful book called The Fireside Book of Chess. This book delights in exuberant comments, such as this:

“Blunders have been made by all classes of chess players – beginners, dubs, tyros, wood-pushers, amateurs, grandmasters and World Champions! Take heart, all of you! For here is an example of an almost incredible blunder made by the most brilliant player that ever lived! Alekhine, conqueror of Capablanca for the World Championship, profound analyst without peer, creator of dazzling combinations, makes a horrible mistake…”

- The tone of excitement in this book was invaluable to me in shaping my own master chess players – and in visualizing Benjamin, who killed himself for love of the sport.